Ortho calculator

References

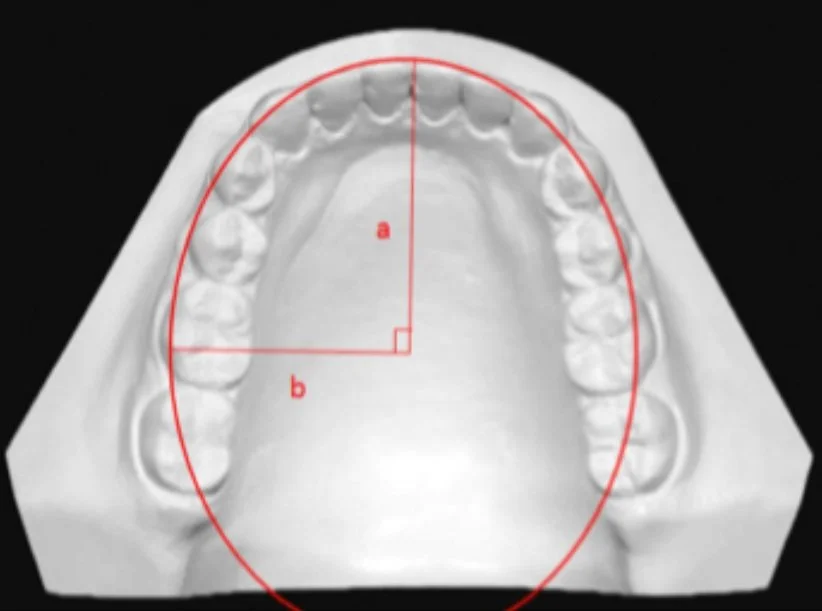

Crowding / Spacing

-

![]()

Assessment

Measure in relation to the line of arch that reflects the majority of teeth.

The Royal London Space Planning: An integration of space analysis and treatment planning. Kirschen et al. 2000.

-

![]()

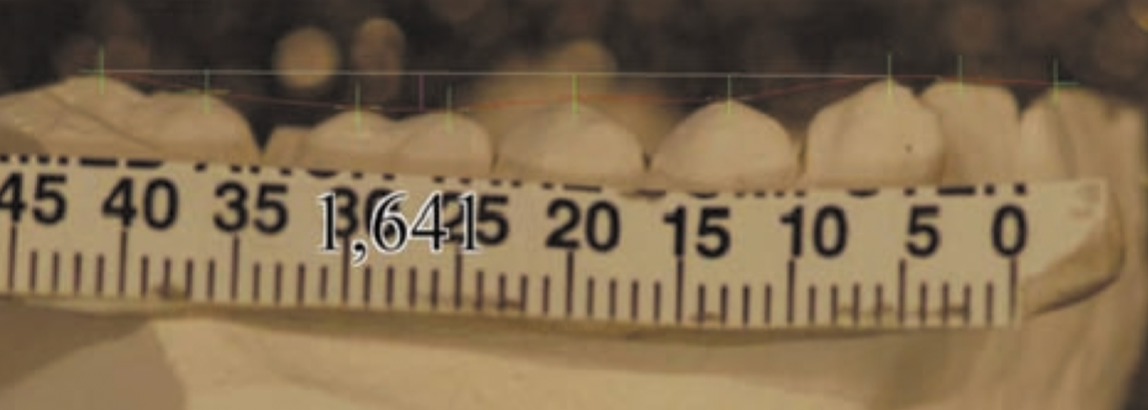

Curve of Spee

Assess the depth of curve from premolar cusps to a flat plane on distal cusps of first molars and incisors. Only one value is given for the arch, and only if the premolars have not been assessed separately as crowded.

Allow 1 mm space for 3 mm depth of curve, 1.5 mm for 4 mm depth, and 2 mm space for a 5 mm curve (usually no allowance is necessary).

The Royal London Space Planning: An integration of space analysis and treatment planning. Kirschen et al. 2000.

-

![]()

Curve of Spee

The arch circumference reduction is considerably less than that found by earlier investigators, implying that the incisor protrusion often associated with leveling the curve of Spee is not primarily due to the aforementioned differential, but rather more directly due to the mechanics used in leveling the curve of Spee.

The curve of Spee revisited. Braun et al. 1996.

-

![]()

Curve of Spee

The results of this study showed that the amount of arch length required to level the curve of Spee is nonlinear and is consistently less than one to one for curves of Spee less than 9 mm. The results also suggest that the belief that 1 mm of arch circumference is necessary to level each millimeter of curve of Spee present is an overestimation.

Arch length considerations due to the curve of Spee: A mathematical model. Germane et al. 1992.

-

![]()

Curve of Spee

Figure 2 considers the incisors as a separate segment that can be moved up or down independently of buccal segment leveling. It can be seen that this independent movement does not necessarily increase arch length requirements, and that the lower anterior teeth are not automatically protruded. […]

If the lower molars are already upright, distal tipping may not be an early requirement for buccal segment leveling. When the teeth are represented as parallel blocks that can slide up or down to fit any curve (Fig. 7), it is evident that buccal segments can be leveled with no increase in arch space requirements.

A reassessment of space requirements for lower arch leveling. Woods. 1986

-

![]()

Leeway Space

The mandibular primary second molar is on the average 2 mm larger than the second premolar; in the maxillary arch, the primary second molar is 1.5 mm larger […] The primary first molar is only slightly larger than the first premolar but does contribute an extra 0.5 mm in the mandible. The result is that each side in the mandibular arch on average contains about 2.5 mm of what is called leeway space; in the maxillary arch, about 1.5 mm is available on average.

Contemporary Orthodontics. Sixth Edition. Proffit.

Planned incisor position

-

![]()

denture positioning

Many Class I treatments the malocclusion may be corrected by tooth alignment only, accepting the position of the upper and lower incisors in the face. This is so-called 'tooth alignment' orthodontics, and it can be straightforward using the preadjusted bracket system. However, the majority of orthodontic cases require changes in incisor position. In addition to 'tooth alignment', most cases require more challenging 'denture-positioning' procedures.

Systemized Orthodontic Treatment Mechanics. McLaughlin, Bennett,Trevisi. 2001.

-

![]()

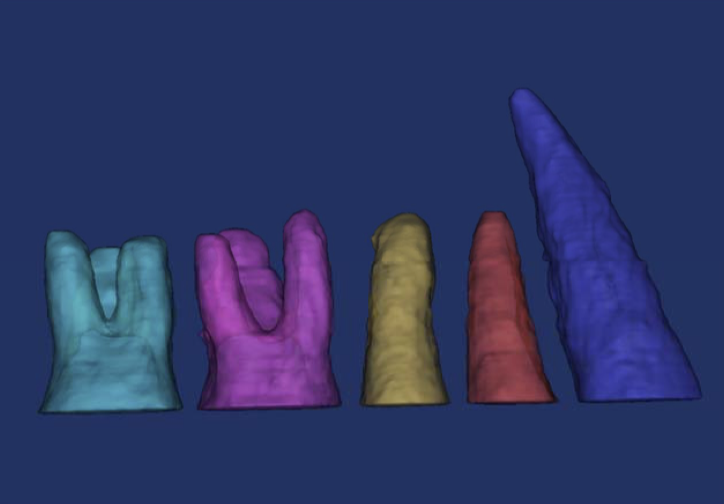

Supporting bones

Nance believed that excessive labial movement of anterior teeth leads to eventual relapse and possible tissue damage: “to line up the teeth in an arch to normal contact point relationships … is downright easy provided one ignores the relationships of teeth to supporting bones.”

Leeway Space and the Resolution of Crowding in the Mixed Dentition. Gianelly. 1995.

-

![]()

Incisor a-p position (na line)

Position the maxillary incisors at 5mm ± 2mm and 22º ± 5º to NA for all skeletal patterns. The measurements increase as the ANB angle decreases, and decrease as ANB increases.

Position the mandibular incisal edges at .5mm ± 2mm to NA and 25º ± 5º to NB , with values decreasing as ANB decreases and increasing as ANB increases.

Where Teeth Should Be Positioned in the Face and Jaws and How To Get Them There. Creekmore. 1997.

-

![]()

incisor a-p position (st glabella)

Most (93%) of the adult white females with harmonious profiles examined in this study had maxillary central incisors positioned anterior to the forehead’s FFA point and posterior to glabella.

AP Relationship of the Maxillary Central Incisors to the Forehead in Adult White Females. Andrews. 2008.

-

![]()

incisor inclination

The most attractive inclination of a tangent to the labial face of the maxillary incisor crowns in profile view in relation to the true horizontal line was 85°, i.e. 5°retroclined from a perpendicular 90°inclination. The most attractive range appears to be between 80 and 90°. Excessive proclination appeared to be less desirable than retroclination.

The maxillary incisor labial face tangent: clinical evaluation of maxillary incisor inclination in profile smiling view and idealized aesthetics. Naini et al. 2019.

-

![]()

incisor inclination

The most preferred smile matched with a maxillary incisor inclined 93 degrees to the horizontal line

Aesthetic evaluation of profile incisor inclination. Ghaleb et al. 2011.

-

![]()

md incisor position

If a threshold at a 50% probability of developing dehiscence was set, then a threshold for L1-NB would be limited to 2.00 mm and, equivalently, for IMPA, a threshold of 8.028. However, it appears that bone loss may begin to increase even earlier, and, thus, these 50% thresholds would be predicted to decrease ABH by about 1.92 mm and ABT by 0.50 mm, on average. For a more conservative threshold of a 10% probability of developing dehiscences with little predicted bone loss, thresholds of L1-NB movement of less than 0.86 mm or an IMPA change of less than 48 could be used.

A cone-beam computed tomographic evaluation of alveolar bone dimensional changes and the periodontal limits of mandibular incisor advancement in skeletal Class II patients. Matsumoto et al. 2020.

Incisor movement

-

![]()

a-p movement

Allow 2 mm space for each mm [Incisor A/P] change. Assess the lower arch first and then correct the upper incisors to overjet 2 mm.

The Royal London Space Planning: An integration of space analysis and treatment planning. Kirschen et al. 2000.

-

![]()

a-p movement

Ricketts et al suggested a 2-mm change in arch perimeter for every 1 mm of anteroposterior movement of incisors.

Ricketts RM, Roth RH, Chaconnas SJ, Schulhof RJ, Engle GA. Orthodontic diagnosis and planning. Denver (Colo): Rocky Mountain Data System; 1982. p. 194-200.

-

![]()

a-p movement

How much will the arch length be decreased by moving the incisors from 11mm back to 4mm? The answer is 14mm, for moving the incisors back this 7mm shortens the arch length 7mm on the left side and also 7mm on the right side, for a total of 14mm. We record this on the minus side opposite “relocation 1”.

The use of cephalometric as an aid to planning and assessing orthodontic treatment. Steiner. 1960.

-

![]()

incisor protrusion

The ellipse is an accurate geometric model of the maxillary arch form. The average amounts of maxillary arch perimeter gained were […] 1.66 mm per millimeter of incisor protrusion.

Maxillary arch perimeter prediction using Ramanujan's equation for the ellipse. Chung et al. 2015.

-

![]()

inclination change

Applies only to maxillary incisors. Allow 1 mm space for every 5°change affecting all 4 incisors, and 0.5 mm space if only 2 teeth are affected. As the space implications are relatively small, the angulation and inclination scores are combined on the space planning form.

The Royal London Space Planning: An integration of space analysis and treatment planning. Kirschen et al. 2000.

-

![]()

mandibular incisor movement

The length of the mandibular dental arch changed in the parabolic arch form by 1.51 mm for each millimetre of incisor inclination with respect to the occlusal functional plane, by 0.54 mm for each degree of controlled tipping and by 0.43 mm for each degree of uncontrolled tipping. In the elliptical arch form (e = 0.78), it changed by 1.21, 0.43, and 0.34 mm, respectively, in the hyperbolic form by 1.61, 0.57, and 0.46 mm, in the circular form by 1.21, 0.43, and 0.34 mm, and in the catenary form by 2.07, 0.74, and 0.59 mm.

A mathematic-geometric model to calculate variation in mandibular arch form. Mutinelli et al. 2000.

-

![]()

proclination

Average gain in arch perimeter by 1mm incisor proclination was 1.67 mm in maxilla and 1.65 mm in the mandible.

Maxillary and Mandibular Arch Perimeter Prediction Using Ramanujan's Equation for the Ellipse-In vitro Study. Aghera et al. 2016.

-

![]()

crowding and incisor movement

Clinicians can expect a 0.5 degree proclination and 0.2-mm protrusion for every millimeter of crowding alleviated by incisor proclination

Relationship between dental crowding and mandibular incisor proclination during orthodontic treatment without extraction of permanent mandibular teeth. Yitschaky et al. 2016.

-

![]()

cos and proclination

Flattening of the COS is mostly achieved by proclination of the mandibular incisors. On average, a 4 degree proclination of the mandibular incisors results in 1 mm levelling of the COS.

Effects of levelling of the curve of Spee on the proclination of mandibular incisors and expansion of dental arches: a prospective clinical trial. Pandis et al. 2010.

-

![]()

space and proclination

Geometrically, every 2.5° of proclination moves the lower incisor incisal edges forward by 1 mm (resulting in space gains of 2 mm for every 2.5° of proclination).

Systemized Orthodontic Treatment Mechanics. McLaughlin, Bennett,Trevisi. 2001.

Expansion

-

![]()

Arch width change

Allow 0.5 mm space for each mm posterior arch width change. An increased amount of space creation can be recorded in cases of rapid palatal expansion.

The Royal London Space Planning: An integration of space analysis and treatment planning. Kirschen et al. 2000.

-

![]()

molar expansion

The average gain in arch perimeter by 1 mm molar expansion was 0.73 mm in maxilla and 0.74 mm in the mandibular arch.

Maxillary and Mandibular Arch Perimeter Prediction Using Ramanujan's Equation for the Ellipse-In vitro Study. Aghera et al. 2016.

-

![]()

RPE expansion

Rapid palatal expansion with the Hyrax appliance produces increases in maxillary arch perimeter at the rate of approximately 0.7 times the change in first premolar width

Arch perimeter changes on rapid palatal expansion. Adkins et al. 1990.

-

![]()

molar expansion

The ellipse is an accurate geometric model of the maxillary arch form. The average amounts of maxillary arch perimeter gained were 0.73 mm per millimeter of intermolar expansion […]

Maxillary arch perimeter prediction using Ramanujan's equation for the ellipse. Chung et al. 2015.

-

![]()

rapid vs slow expansion

Regression analysis indicated that arch perimeter gain through the treatment could be predicted as 0.65 times the amount of the posterior expansion for the RME group and 0.60 times the amount of posterior expansion for the SME group.

Comparison of dental arch and arch perimeter changes between bonded rapid and slow maxillary expansion procedures. Akkaya et al. 1998.

-

![]()

mandibular uprighting

A 1 mm increase in arch width resulted in an increase in arch perimeter of 0.37 mm. This result would be of value clinically for prediction of the effects of mandibular expansion.

An experimental study on mandibular expansion: Increases in arch width and perimeter. Motoyoshi et al. 2002.

-

![]()

B-L inclinations

In order to establish proper occlusion in maximum intercuspation and avoid balancing interferences, there should not be a significant difference between the heights of the buccal and lingual cusps of the maxillary and mandibular molars and premolars.

Objective grading system for dental casts and panoramic radiographs. Casko et al. 1998.

-

![]()

Crossbites

A flowchart for determining the appliance used for treating individual or segment of teeth in crossbite.

Orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning in the primary dentition. Ngan and Fields. 1995.

-

![]()

Palatal width

Patients with maxillary transverse deficiency usually have a narrow palate and a posterior crossbite. If the maxilla is narrow relative to the rest of the face, a diagnosis of transverse maxillary deficiency is justified. […] a narrow maxilla accompanied by a narrow mandible and normal occlusion should not be considered a problem just because the jaw widths are below the population mean.

Contemporary Orthodontics. Sixth Edition. Proffit.

-

![]()

arch coordination

[…] the palatal cusps of the maxillary molars should intercuspate with the fossae and marginal ridges of mandibular molars, the buccal cusp of the mandibular premolars should intercuspate with the marginal ridges of the maxillary premolars, and the mandibular canines and incisors should intercuspate with marginal ridges of the maxillary canines and incisors. The maxillary teeth should be upright and centered in the alveolar/basal bone and coordinated with the mandibular teeth, which should also be upright and centered in the alveolar/basal bone to obtain a proper intercuspation.

Orthodontics, Current Principles and Techniques. Sixth Edition. Graber et al.

space creation

-

![]()

u6 derotation

The mean arch length gain anterior to the maxillary first molar, when the center of rotation is at the center of a lingual attachment, is 2.1 mm at a maximal derotation angle of 18°.

The effect of maxillary first molar derotation on arch length. Braun et al. 1997.

-

![]()

limits of distalization

Posterior anatomic limit for total distalization. A and B, The available space at the maxillary tuberosity distal to the second molars, and the available space between the mandibular second molar and the anterior border of the ramus in the sagittal plane; C and D, the available space between the second molar crown to the anterior border of the ramus and between the root to the inner lingual cortex of the mandible in the axial plane.

Total intrusion and distalization of the maxillary arch to improve smile esthetics. Baek et al. 2016.

-

![]()

mx Tuberosity as limit for distalization

In the biological aspect, the following should be considered: the necessary space in the maxillary tuberosity area to move the teeth distally […] In this patient, the maxillary third molars were extracted before orthodontic treatment to allow sufficient space in the maxillary tuberosity area to distalize the teeth.

Total distalization of the maxillary arch in a patient with skeletal Class II malocclusion. Choi et al. 2011.

-

![]()

lingual cortex of md body as limit for distalization

The posterior available space was significantly smaller at the root level than at the crown level. […] The posterior anatomic limit appeared to be the lingual cortex of the mandibular body. Mean distances between the root and the inner and outer lingual cortexes at a level of 10 mm from the cementoenamel junction were 2.87 and 6.73 mm, respectively. Considering that the reasonable amount of molar distalization is approximately 3 mm, the available space appeared to be appropriate. However, individual variations were considerable; a third of the mandibular second molar roots were in contact with the inner lingual cortex, rendering distalization an unfeasible treatment option in these cases.

Mandibular posterior anatomic limit for molar distalization. Kim et al. 2014.

-

![]()

IPR

50% of proximal enamel is the maximum amount that can be stripped without causing dental and periodontal risks […] 1 mm (.5 mm per proximal surface) can be removed from the contact points of the buccal section, while stripping of the lower incisors should not exceed .75 mm at each contact point due to the thinner proximal walls. Nonetheless, the orthodontist should not underestimate the variations in proximal enamel thickness among tooth categories and ethnic groups, and customize the enamel surface preparation according to individual’s characteristics.

Enamel Reduction Techniques in Orthodontics: A Literature Review. Livas et al. 2013.

-

![]()

md posterior ipr

There was approximately 10 mm of total enamel on the four teeth combined. Assuming 50% enamel reduction, the premolars and molars should provide 9.8 mm of additional space for realignment of mandibular teeth.

Enamel thickness of the posterior dentition: its implications for nonextraction treatment. Stroud et al. 1998.

-

![]()

ipr

Up to 4 to 6 mm can be created with interproximal reduction of teeth, usually done on the incisors and less often the canines and premolars. If more than 6 mm of space is required, extraction of premolars could be indicated.

Orthodontics, Current Principles and Techniques. Sixth Edition. Graber et al.

Extractions

-

![]()

Rules of Thumb

Rule of thumb: Canine extractions net approximately 15mm. The entire extraction space can be used for incisor alignment and retraction, since the posterior teeth will not move forward at all.

Rule of thumb: Ordinarily, when mandibular first bicuspids are extracted, you can expect the posterior teeth to come forward about one-third of the space (about 2.5mm on each side), leaving two-thirds of the space (about 5mm on each side) for correction of crowding and for incisor retraction.

Rule of thumb: Ordinarily, when mandibular second bicuspids are extracted, you can expect the posterior teeth to come forward about half the extraction space. This nets about 7.5mm for correction of the crowding and retraction of the anterior teeth.

Where teeth should be positioned in the face and jaws and how to get them there. Creekmore. 1997.

-

![]()

Differential anchorage

If all bone offered the same resistance to tooth movement, the anchorage potential of maxillary and mandibular molars would be about the same. Clinical experience shows that maxillary molars usually have less anchorage value than mandibular molars in the same patient. A common example is space closure in a Class I four premolar extraction case; it often is necessary to use headgear on the maxillary first molars to maintain the Class I relationship. The relative resistance of mandibular molars to mesial movement is a well-known principle of differential mechanics.

Orthodontics, Current Principles and Techniques. Sixth Edition. Graber et al.

-

![]()

Space from various extractions

All other factors being equal, the amount of incisor retraction will be less the further posteriorly in the arch an extraction space is located.

Contemporary Orthodontics. Sixth Edition. Proffit.

-

![]()

mx space closure

The 4/4 and 4/5 subgroups had mean incisor retractions of 4.2 mm and 3.7 mm, respectively, whereas the 5/5 group had a mean retraction of 2.3 mm.

Anteroposterior changes in the maxillary first molar position are shown in Table 8 […] Mean changes in the estimated molar movement were not found to be significantly different among the groups.

An Occlusal and Cephalometric Analysis of Maxillary First and Second Premolar Extraction Effects. Ong & Woods. 2001.

-

![]()

md space closure

There is generally more forward movement of the lower molars than incisal retraction with the extraction of lower second premolars than with the extraction of lower first premolars, although a specific extraction pattern does not necessarily guarantee certain amounts of incisor retraction or lower molar forward movement.

The 4/4 group had the greatest mean incisor retraction of 2.4 mm, whereas the 4/5 and 5/5 had mean retractions of 1.4 mm and 0.5 mm, respectively.

An occlusal and cephalometric analysis of lower first and second premolar extraction effects. Shearn & Woods. 2000.

-

![]()

second premolar exos

Most orthodontists agree on second-premolar extraction in cases presenting some crowding when they deliberately want to move the molars forward more than 2.5 mm. on each side, perhaps, from 3 mm. to 4.5 mm. or, in other words, they want to slip or lose part of the anchorage.

Second-premolar clinical practice. de Castro. 1974.

-

![]()

all 4s vs all 5s

Group 2 [second premolar extractions] showed more mesial movement of the maxillary and mandibular first molars and less retraction of the upper and lower central incisors than group 1 [first premolar extractions].

First or Second Premolar Extraction Effects on Facial Vertical Dimension. Kim et al. 2005.

-

![]()

differential premolar extractions

The results indicate that, on average, maxillary retraction in relation to the facial plane (N Po) differed only slightly between group 55 (mean 4.2 ± 2.4 mm) and group 44 (mean 4.7 ± 2.3 mm), with relatively more retraction for group 45 (mean 6.6 ± 2.5 mm; p < 0.05). In contrast, the mandibular incisors were retracted slightly more in group 44 than in the other two groups (p < 0.05).

Differential premolar extractions. Steyn & Harris. 1997.

-

![]()

All 5s space closure

The mean incisor movements were 3.3 and 2.9 mm lingually in the maxilla and the mandible, respectively. The first molars were moved mesially an average of 3.2 and 3.4 mm in the maxilla and the mandible, respectively. […] Zigzag elastics (Class II elastics and intra-arch elastics) were applied to close the remaining extraction spaces and harmonize the molar relationship.

Tooth movement after orthodontic treatment with 4 second premolar extractions. Chen et al. 2010.

-

![]()

U4 Space Closure based on Root surface area

Exclusion of the second molars in a maxillary 1 st premolar extraction scenario results in 50% anterior to posterior anchorage ratio, and reciprocal space closure with equal movements of the anterior and posterior segments is expected.

The Use of CBCTs to Determine Relative Anchorage Values by Measuring Maxillary Root Surface Areas within Bone. Stateson, 2019.

-

![]()

U4 space closure

A four first premolar extraction pattern in Class I patients provides space that is consumed almost equally by the retraction of canines and the mesial movement of the buccal segments in the maxilla.

Bowles, Ryan Gregory , "First Premolar Extraction Decisions and Effects" (2005). Theses and Dissertations (ETD). Paper 30.

-

![]()

All 4s vs all 5s

Extraction pattern is the most significant, where mean canine retraction was 3.4 mm in the first-premolar extraction sample compared to the 2.3 mm observed in the second-premolar extraction sample.

The first-premolar extraction sample’s first molar moved forward an average of 4.0 mm, whereas the first molar moved forward an average of 4.7 mm in the second-premolar extraction sample.

Turner, Robert A. , "Quantitative Analysis of First- versus Second-Premolar Extraction Effects in Orthodontic Treatment" (2007). Theses and Dissertations (ETD). Paper 268.

-

![]()

extraction pattern & incisor retraction

In the maxillary and mandibular first premolar extraction cases, […] it was found that approximately 66.5 per cent of the available extraction space was occupied by the retracted anterior segments (Table IV).

The cases involving extraction of the maxillary first premolars and the mandibular second premolars […] there was slightly less mean anterior retraction in this type of treatment as compared to the maxillary and mandibular first premolar cases. Approximately 56.3 per cent of the available extraction space was taken up by retraction of the anterior segments (Table V).

The effect of different extraction sites upon incisor retraction. Williams & Hosila. 1976.